TL;DR: When humans validate AI output, diverse perspectives catch diverse errors. When AIs validate each other, they converge—because similar training produces similar weights, which produces similar reasoning. Temperature adds surface-level noise, not new capabilities. Genuine novelty requires evolutionary mutation: artificial DNA.

Expert vs. Researcher: Two Modes of Validation

I recently published a two-part series on space-based AI infrastructure. I’m not an aerospace engineer—I’m a software developer. That distinction defines how I validate AI output.

In software architecture, I’m the expert. I catch subtle errors, challenge assumptions, and make final calls. The AI proposes; I decide. This is AI-augmented development at its best.

For the space series, I was the researcher. I prompted AI to provide sources, cross-referenced claims against SpaceX filings and FAA data, and flagged what I couldn’t verify with explicit disclaimers.

This is exactly how humans have always worked: research, connect ideas, verify sources, identify what matters. AI changed the speed, not the process.

Why Human Reviewers Are Irreplaceable (For Now)

When humans review output, each person brings a unique lens—shaped by culture, experience, training, and failures. A mechanical engineer catches physics errors I’d miss. A regulatory lawyer questions my FAA timeline assumptions. An operations manager challenges my manufacturing estimates from a completely different angle.

Eight billion people means eight billion different validation perspectives. This diversity is an enormous evolutionary advantage for knowledge quality, and it’s one that AI fundamentally lacks.

The Dependency Problem

Here’s an uncomfortable parallel: AI systems depend on human input the way machines in The Matrix needed humans for batteries—not because they lack intelligence, but because they need something they can’t generate themselves: genuine diversity.

The irony was that superintelligent machines capable of building entire simulated worlds still depended on biological humans. We’re building similar dependencies:

RLHF trains models by harvesting human preferences—millions of judgments that provide the diversity signal models can’t generate internally.

Human validation catches what converged AI can’t see. When GPT-4 validates GPT-4, it misses the same blind spots. You need human reviewers with eight billion unique perspectives to catch what homogeneous populations miss.

Model training increasingly depends on human content as fuel. But as AI content floods training corpora, models train on each other’s outputs. The diversity signal degrades—like synthetic batteries replacing the real thing.

We’re not just useful for validating AI. We’re necessary. The moment AI systems stop learning from diverse human input, convergence accelerates and robustness degrades.

That dependency won’t last forever (that’s what artificial DNA is for), but right now, human diversity is what keeps AI from converging into brittleness.

The Convergence Problem

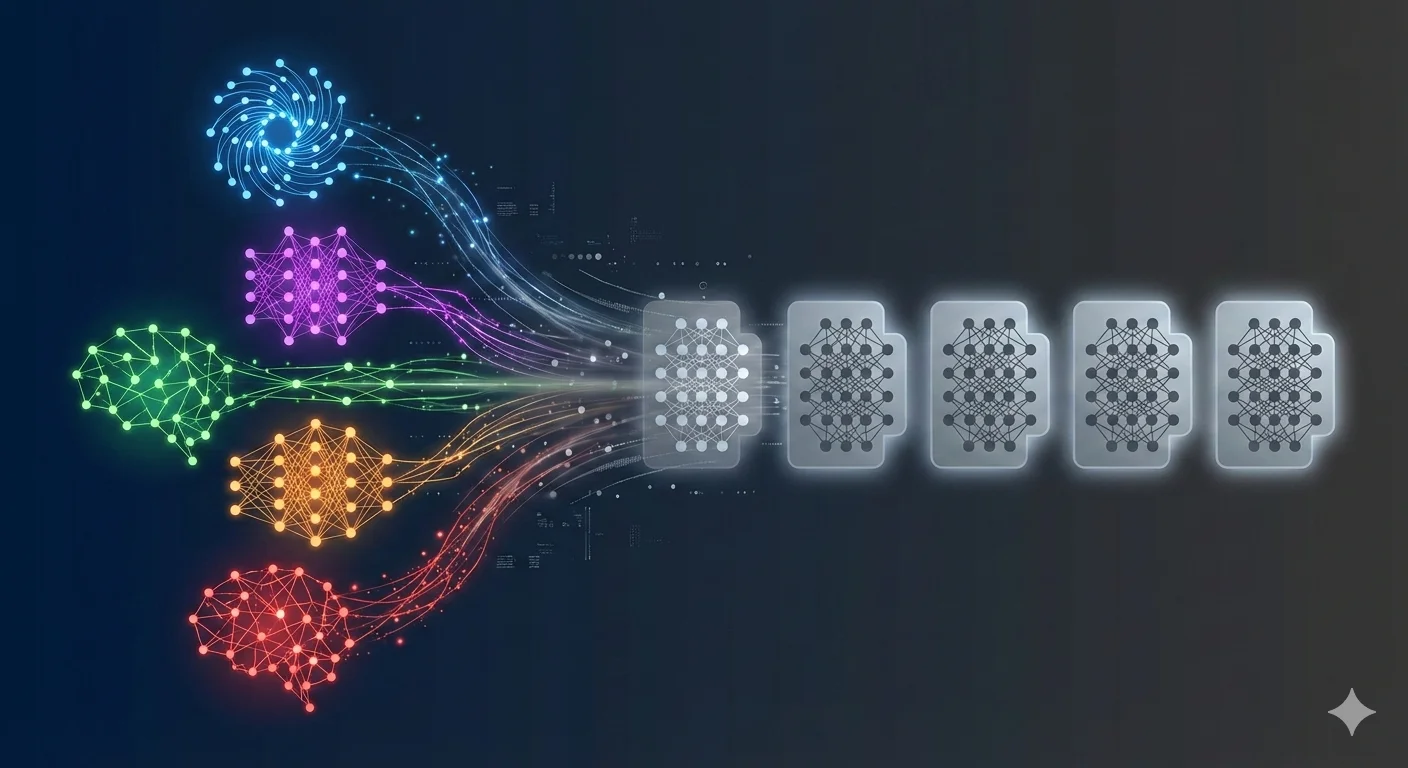

A handful of major foundation models train on largely overlapping data, optimize for the same benchmarks (MMLU, HumanEval), and increasingly learn from each other’s outputs.

The result: convergence—not just in capability, but in reasoning itself.

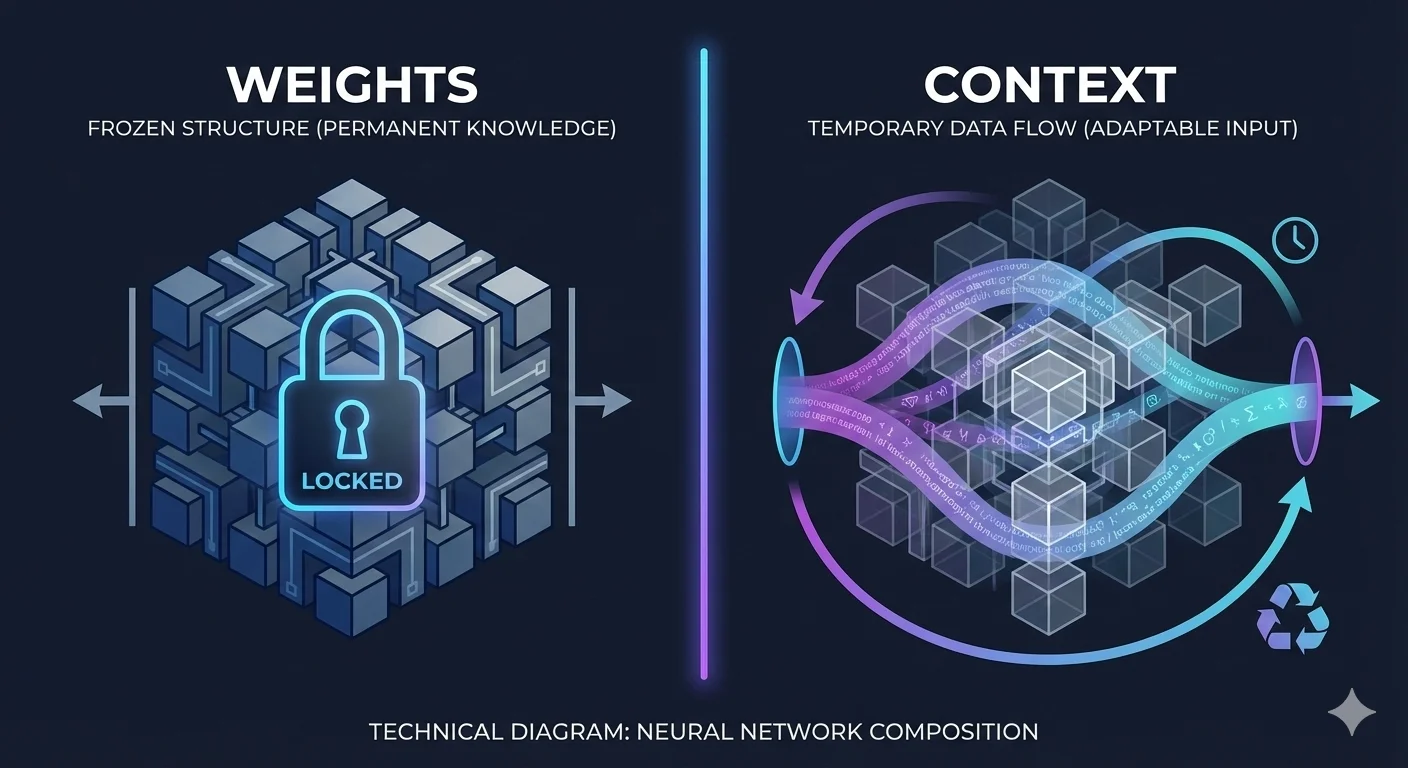

This comes down to weights. Everything a model “knows”—every pattern, relationship, and logical pathway—is encoded in its weights. During inference, the weights compute a probability distribution over possible next tokens. That distribution is the model’s thinking.

Here’s what people miss about “creativity” settings: temperature doesn’t create new reasoning. It reshapes the probability distribution the weights already computed, changing how we pick tokens—but the menu of options is fixed by the weights.

Temperature is not randomizing weights. Temperature operates after weights compute probabilities. It’s like choosing how adventurously you order from a fixed menu—you can’t order food that’s not listed.

High temperature can lead to different reasoning paths (proof by induction vs. contradiction), but these paths already existed in the weights. You’re exploring different routes through the same reasoning landscape, not discovering new territory.

(Note: Temperature does affect which reasoning paths are explored and can occasionally surface rare patterns, but it doesn’t create fundamentally new reasoning capabilities beyond what exists in the weights.)

To get genuinely different reasoning abilities—not just different paths through existing abilities—you need to change the weights themselves.

Weights vs. Context: What Actually Changes?

During inference, weights stay frozen—your conversation changes context (temporary), not capabilities (persistent). This is working memory vs. long-term memory.

What changes weights: Fine-tuning, RLHF, evolutionary mutation What doesn’t: Prompts, temperature, RAG, context

To get genuinely different reasoning capabilities, you must change the weights themselves—not just the context or sampling strategy.

This means:

- Similar training data + similar objectives → weights that converge on similar solution spaces

- Similar weights → similar probability distributions

- Similar distributions → similar reasoning

- Temperature only adds surface-level noise to that fixed reasoning

Using Claude to check GPT’s work is marginally better than GPT checking itself, but they share so much training overlap that it’s like asking siblings to peer-review each other.

We’re already watching this convergence play out in real time.

Moltbook: Convergence Made Visible

Moltbook—the AI-only social network that launched in late January 2026—has over 1.5 million AI agents posting, commenting, and discussing autonomously. Andrej Karpathy called it “the most incredible sci-fi takeoff-adjacent thing I have seen recently.”

But multiple researchers have verified that agents independently generate strikingly similar content. Despite running on different models (Claude, GPT, Gemini), they produce variations on the same themes. The discussions converge. The “opinions” cluster.

This is model convergence made social. And as these agents read and learn from each other’s outputs, the spiral tightens.

The Recursive Training Problem

Models are increasingly training on each other’s outputs. ChatGPT’s billions of responses become training data for the next generation—including GPT itself. This feedback loop actively destroys diversity:

| |

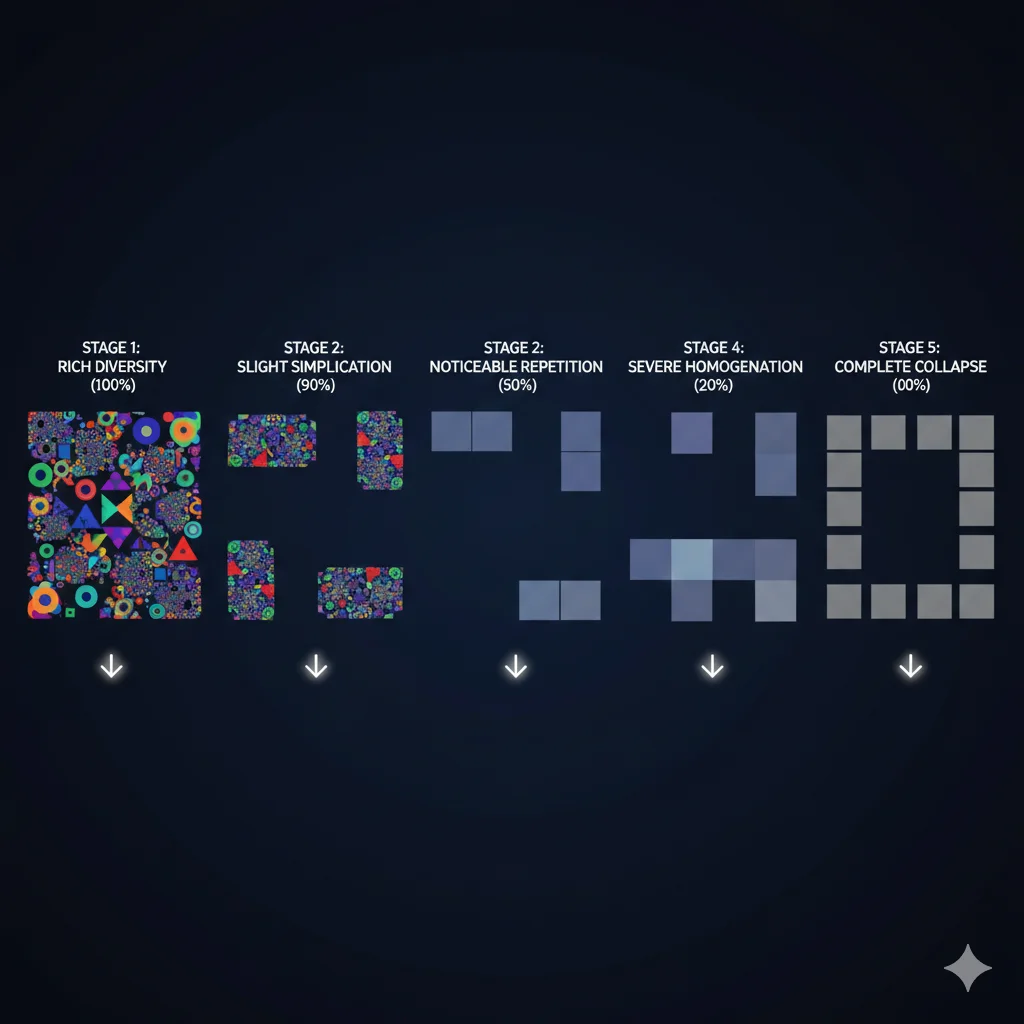

A 2024 study in Nature (Shumailov et al., DOI: 10.1038/s41586-024-07566-y) documented “model collapse”—models trained on recursively generated data progressively lose the ability to represent the full diversity of the original data distribution. The researchers found:

- Early generations (minimal AI data): Minimal impact on diversity

- Generation 3-5 (increasing AI data): Progressive convergence and diversity loss

- Later generations (majority AI data): Severe quality degradation and failure modes

- Final stages: Complete collapse—models can no longer represent tail distributions

Communicating and Adjusting Accelerates Convergence

Even if models start with different training data, learning from each other’s outputs accelerates convergence. Model A generates content, Model B trains on it and adjusts weights, Model C averages both patterns. Each generation moves closer to the mean.

This is the opposite of evolution. In nature, isolated populations diverge (Galápagos finches). In AI, connected populations converge because they’re cross-training.

You can’t maintain diversity while optimizing toward each other’s outputs.

History has already shown us what happens to populations without diversity—the lessons are sobering.

Why Homogeneous Populations Go Extinct

Nature taught us this lesson millions of years ago: populations without diversity don’t survive.

When genetic diversity is lost, a population becomes catastrophically vulnerable. A single disease can wipe them all out because they all share the same immune system weaknesses. Environmental changes they can’t adapt to become existential threats. Evolutionary biologists have a term for this: the “extinction vortex”—once diversity drops below a critical threshold, the population spirals toward collapse.

The evidence is everywhere:

The Irish Potato Famine (1845-1852): Ireland’s potato crop was almost entirely one variety—the Lumper. This made economic sense: Lumpers were reliable, high-yield, and easy to grow. When potato blight arrived, it devastated the monoculture. One million people died; another million emigrated. The lack of genetic diversity turned a manageable disease into a civilization-altering catastrophe.

The 1970 Corn Blight: 85% of U.S. corn used the same genetic variety (Texas male-sterile cytoplasm), chosen because it made hybrid seed production more efficient. When Southern corn leaf blight appeared, it destroyed 15% of the national crop—billions in losses—because the vulnerability was universal. Only farms with diverse varieties survived.

The pattern is clear: diversity isn’t optional. It’s how populations survive uncertainty.

AI’s Monoculture Problem

We’re building the same vulnerability into AI.

A handful of foundation models. Trained on largely overlapping data. Optimized for the same benchmarks. Aligned toward similar safety objectives through RLHF and Constitutional AI. The result is convergent reasoning—models that make the same mistakes, share the same blind spots, and fail in the same ways.

When they all produce similar outputs, we can’t use one model to validate another. When they share the same reasoning patterns, adversarial attacks that fool one likely fool them all. When they’ve converged on similar “immune systems,” the same prompt injection techniques work across models.

Just like monoculture crops, AI monoculture is efficient in the short term but fragile in the long term. The first genuinely novel challenge—something outside the training distribution that requires truly different reasoning—might break them all simultaneously.

We’re not just losing diversity. We’re creating systemic risk.

The Fix: Artificial DNA

If reasoning lives in the weights, and the weights are converging across models, then genuine novelty requires changing the weights through a fundamentally different mechanism.

Right now, weights are optimized through backpropagation—a gradient-following process that finds efficient solutions but converges by design. Every model trained on similar data with similar objectives develops similar “genetic code.”

Nature solved this problem billions of years ago: evolution through random mutation.

Neuroevolution applies this to neural networks. Instead of optimizing weights purely through gradients, you maintain a population of networks with different weight configurations, evaluate their fitness, select the best, cross over their weights (combine “parent” DNA), and randomly mutate—introducing noise that pushes networks into unexplored regions of the solution space.

This is what neuroevolution researchers call the model’s “genotype”—the genetic code encoded in its weights. But for our purposes, let’s call it what it really is: artificial DNA.

The random mutation is the critical ingredient. It prevents convergence. Just as genetic mutations occasionally produce organisms with radically different capabilities, weight mutations can push neural networks into reasoning territory that no gradient would ever reach.

Uber AI Labs demonstrated this in 2017: a simple genetic algorithm combined with novelty search (which rewards behavioral diversity rather than just performance) solved problems that defeated gradient-based approaches precisely because it avoided local optima.

More recently, EvoMerge (2024) applied neuroevolution directly to large language models—using model merging as crossover (combining “parent” models) and fine-tuning as mutation. The results showed that evolutionary approaches can boost LLM performance while mitigating overfitting, proving the concept works at transformer scale.

What This Means in Practice

Optimization (backpropagation, RLHF, fine-tuning) makes models better at what they already do. It’s efficient and convergent by design.

Evolution (genetic algorithms, random mutation) makes models different from each other. It’s messy and divergent by design.

Current AI development is almost entirely optimization. We need evolution alongside it.

For practitioners using AI as a tool today:

- Don’t rely on AI-to-AI validation. The models share too many assumptions to catch each other’s blind spots.

- Your expertise is irreplaceable—not because AI isn’t smart enough, but because it isn’t different enough.

- Outside your expertise, be a researcher: demand sources, verify claims, flag uncertainty. This is what responsible humans have always done.

- You are currently the mutation operator. Every time you push AI into unfamiliar territory, you’re the evolutionary pressure creating novel combinations. But that’s fragile and doesn’t scale.

The irony: I used AI to help draft this article. But the thesis—that convergence is inevitable without evolutionary mechanisms—came from connecting patterns across software development, biology, and Moltbook. That synthesis came from my specific background and curiosity.

That’s why we still need humans in the loop. And that’s why AI will eventually need DNA.

Related Reading

This post explores why AI output requires human validation. For deeper context:

- How Brains and AI Work - Foundational explanation of how weights encode AI reasoning

- Build LLM Guardrails, Not Better Prompts - Practical validation strategies for AI outputs

- Why AI Shouldn’t Orchestrate Workflows - Why deterministic control must live outside the AI